A young girl runs outside the village of Ngop in the Unity state, South Sudan, at sunset. NRC distributed food to more than 7,100 people in Ngop to mitigate the high risk of famine. NRC/Albert Gonzalez Farran, March 2017

Every year, floods, storms, earthquakes and other natural hazards force millions of people to abandon their homes, a level of displacement greater than that associated with conflict and other forms of violence. Two-thirds of all new internal displacements in 2020, or 30.7 million [i], were disasters, mostly storms and floods. Leaving one’s home can be the first of many further disruptions to people’s lives: they may be forced to move multiple times once they become displaced, and it can be months or even years before they can return home. Those who do return often face unsafe conditions and the prospect of becoming displaced again by the next disaster.

More than 20 years after the Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement were published, researchers and policy-makers agree that looking backwards is insufficient to inform policies and actions to reduce future displacement risk.[ii] If displacement is only understood through analyses of what has happened in the past, protection and assistance measures will only be able to address current situations. In other words, when displacement is only accounted for and addressed after it happens, responses are largely limited to humanitarian, relief and protection interventions. If, on the contrary, retrospective analysis is complemented with probabilistic analyses and metrics – assessments of the likelihood of certain displacement events taking place within a specific future timeframe – new opportunities for action open up.

Adding a dimension of how our future climate will affect the frequency and intensity of hazards, we enter into unknown territory. Research shows that even if the world’s population were to remain at its current level, the risk of flood-related displacement would increase by more than 50 per cent with each degree of global warming.[iii] For the first time, there is broad agreement among scientists that climate change in combination with other factors is likely to increase future displacement.[iv]

Climate change has been proven to make certain hazards in some regions more frequent and intense.[v] Weather events such as floods, storms and drought account for more than 89 per cent of all disaster displacement.[vi] Not all weather-related disasters and their associated displacement, however, are directly related to climate change. Non-extreme events can also trigger disasters and displacement.[vii] But climate change can be understood as a displacement trigger in its own right when coastal land is lost to sea level rise and coastal erosion. It is a visible aggravator when livelihoods are eroded by soil degradation and loss of ecosystem services, and a hidden aggravator that increases the intensity of storms and shifts rainfall patterns that result in floods. It can also intensify the negative impacts of displacement.[viii]

The European Commission (EC)-funded HABITABLE project aims to advance our understanding of the current interlinkages between climate impacts and migration and displacement patterns and better anticipate their future evolution. The Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC) brings its unique expertise as one of the world’s definitive sources of data and analysis on internal displacement. Since our establishment in 1998 as part of the Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC), we have offered a rigorous, independent and trusted service to the international community. Our work informs policy and operational decisions that improve the lives of the millions of people living in internal displacement or at risk of becoming displaced in the future.

With more than 15 years of experience monitoring and analysing internal displacement, regardless of its scale, we have developed innovative, specialised tools to expand our global coverage and to continuously improve our understanding of disaster displacement.

Under Work Package 3 of the Habitable project, we will support the development of models to produce empirically calibrated estimations of future human mobility for both sudden-onset hazards and slow-onset hazards as the effects of climate change deepen.

Accounting for future displacement risk

IDMC began a unique probabilistic modelling exercise for sudden-onset hazards in 2017 with its global disaster displacement risk model, which assesses the likelihood of such population movements in the future. Since 2011, the UN Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR) has rigorously analysed the risk of economic losses from disasters in its Global Assessment Report (GAR).[ix] One critical gap, however, concerns evidence and analysis of the risk of disaster-related displacement, a problem which hinders the effective reduction of both displacement and disaster risk.

The risk assessment developed in 2017 considers a large number of possible scenarios, their likelihood, and the associated damages to housing. Our risk model is informed by and relates to medium- to large-scale events, but small and recurrent events still require the daily monitoring of empirical information to understand the true historical scale of displacement.

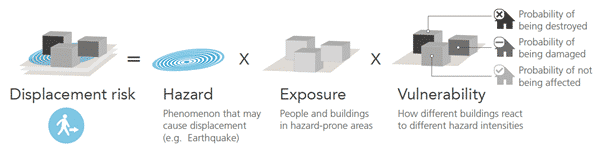

Our Displacement risk model is determined by three factors:

- Hazard: the likelihood of different hazards and their intensity

- Exposure: the number of people and assets exposed to hazards

- Vulnerability: the likelihood of exposed buildings being rendered uninhabitable as a proxy for displacement

The results are a probabilistic indication of the potential impact of events, but underlying limitations and simplifications mean the figures for individual events and the impacts on particular assets are unlikely to be precise.

Our current model uses a step function to assess vulnerability. A certain damage to dwellings or a certain rise in water levels provide the necessary information to assess the likelihood that people will remain in their homes or not.

The model, in short, does not consider people’s economic and social vulnerability. It covers only the physical aspect of vulnerability by examining the extent of damage and destruction that hazards of different intensities are likely to cause (see figure 1).

Given that people’s level of vulnerability and exposure to hazards does much to determine the severity of impacts, however, it is important to assess how these aspects will change over space and time, and to unpack the economic, social, environmental and governance factors that affect disaster risk.

To do so, IDMC works closely with partners to obtain better data on risk exposure and rethink its way of assessing vulnerability in the displacement risk equation. As “riskscapes” evolve constantly, we need to understand population and socioeconomic patterns, as well as fluctuations in the frequency and intensity of hazards linked to climate change.

We will assess the risk of displacement for floods in Ethiopia, Somalia and Sudan within the Habitable project, using the latest data available, a more accurate vulnerability function, and a more granular resolution for hazard and exposure. Vulnerability is a dynamic concept, composed of various dimensions, all of which need to be considered in a holistic vulnerability assessment. Vulnerability and risk assessments for slow-onset hazards, such as drought and desertification, might require a different approach.

Not a matter of choice; displacement associated with drought situations

The direct and indirect impacts of drought pose major challenges for populations depending primarily on natural resources and can generate major disruptions in people’s livelihoods, food security, economies and ecosystems.[x] Displacement triggered by droughts results when the direct or indirect impacts of drought push communities to critical thresholds and erode traditional coping strategies (such as mobility), making some livelihoods unsustainable or non-viable.[xi] Drought and its impacts are among the most complex hazards to monitor, more complex than sudden-onset disaster events. Understanding the development and characteristics of drought events and their societal impacts is crucial to anticipating the risk of droughts’ negative impacts, reducing them, and improving emergency responses and drought risk reduction and preparedness actions. Only with a thorough understanding of drought displacement drivers and triggers, can effective assistance strategies, prevention measures and drought displacement risk assessments be implemented and improved.

In recent decades, academics and operational actors have tried to understand and model drought as a trigger of displacement. Few projects or academic publications, however, have focused on the modelling of internal displacement triggered by drought from a data-driven perspective.

As part of the Habitable project, and with additional support from the German Federal Foreign Office, IDMC conducted a unique overview of state-of-the-art drought displacement modelling and compared the strengths and weaknesses of different approaches.[xii] IDMC also did an in-depth assessment of the availability of data for the modelling of drought phenomena in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Drought displacement modelling is a relatively new field. It is very much underrepresented in drought-related human mobility modelling to which advanced methodologies have been applied only over the last decade (e.g., ABMs, Bayesian Networks and other Machine-Learning techniques). Current limitations and challenges in modelling drought displacement can be summarized as three main factors: a lack of data availability and access, the need to improve existing methodologies to model drought-related mobility, and the lack of understanding on the processes that lead to drought displacement in context specific situations.

Recent advances in data acquisition methods related to displacement monitoring, Earth observation using satellite imagery, and the appearance of alternative data sources have boosted the potential and development of novel techniques to model and quantify the impacts of events and forecast drought displacement. As a result, IDMC decided to explore a novel modelling approach in partnership with universities and research foundations to estimate internal displacement triggered by drought that combines different approaches.

This approach builds on lessons learned from previous exploratory modelling exercises done by IDMC in 2014 that consisted of the modelling of displacement risks for Kenyan, Ethiopian and Somali pastoralists. It also involves an update of that model, carried out in 2021 in partnership with the Danish Refugee Council using a system dynamics approach.[xiii] The novel approach explores drought as a trigger of displacement that is not restricted to pastoralist livelihoods.

Understanding and modelling the different links between drivers of drought, displacement, human mobility and climate change requires interdisciplinary collaborative approaches. So does validating the scenarios and results of projections and forecast models. At IDMC, we are committed to continue bringing together technical, domain knowledge and community experts. It is only through this approach that we can achieve much-needed improvements in displacement modelling.

References

[i] IDMC, 2021 Global Internal Displacement Report, 2021

[ii] OCHA, Guiding principles on Internal displacement, 1998

[iii] ETH Zurich, Climate change significantly increases population displacement risk, 2021

[iv] IPCC, Climate Change 2014. Synthesis Report, Summary for Policymakers” 2014

[v] IPCC, Climate Change widespread rapid and intensifying, 2021

[vi] IDMC, 2021 Global Internal Displacement Report, 2021

[vii] IPCC, The IPCC Special Report on Managing the Risks of Extreme Events and Disasters to Advance Climate Change Adaptation 2012

[viii] Science, Addressing the human impact in a changing climate, 2021

[ix] UNDRR, Annex 1 GAR Global Risk Assessment: data, sources and usage, 2013

[x] UNDRR, GAR Special Report on Drought, 2021

[xi] IDMC, No matter of choice: displacement in a changing climate, 2018

[xii] IDMC, The state-of-the-art on drought displacement modelling, 2022 (to be published in May 2022)

[xiii] IDMC, Assessing drought displacement risk for Kenyan, Ethiopian and Somali pastoralists, 2014