Disclaimer: this short article is mainly based on CARE’s report “Evicted by Climate Change : Confronting the gendered impacts of climate-induced displacement”

Introduction

The impacts of climate change and climate-related forced displacement are not gender neutral, nor are the solutions. The populations most affected by climate disruption are mostly in countries of the global South, that contribute the least to the problem. The injustice is further exacerbated for women and girls, as systemic gender inequalities limit their participation in decision-making, access to education, access to and control over resources, and their choice to migrate.

CARE’s work with communities across the world in close to 100 countries has shown that women and girls are also actors of change, who develop and implement innovative solutions and accelerate household and community-level resilience building. It has become crucial to better understand gender roles, including the power relations between women and men, and how these factors influence vulnerability to climate change and climate-related displacement. These factors will be explored through the H2020 HABITABLE project, which aims to significantly advance our understanding of the current interlinkages between climate impacts and migration and displacement patterns, including by empirically investigating the gendered and social dynamics around these impacts.

There is also an urgent need to scale-up gender-transformative adaptation (1) to climate change , beyond mere gender sensitivity, to support more gender equal and resilient communities. CARE calls on all actors, including academia, governments, the private sector and civil society organizations, to contribute to a safer, more inclusive and resilient future for all.

What climate-induced displacement means for women and girls

Climate change impacts generally amplify pre-existing gender vulnerabilities due to geographic, cultural, traditional, religious, socio-economic factors and practices. In many countries, women in rural areas are highly dependent on natural resources, such as water or firewood, for agriculture work. This work is a source of income and a means of feeding and providing for their family, which they are largely responsible for. With climate change and environmental degradation, these resources become scarce and increase the families’ workload. Women and girls, who are traditionally tasked with fetching water, must walk much longer distances to get to rare water access points. It puts them at risk of violence during the long daily walks and reduces the time that they can invest in their own education or in income-generating activities. In addition, women often have little or no access to decision-making in their households and communities and, due to low levels of education, do not have access to information about pending disasters. Moreover, systems to tackle disaster or to adapt are not built for them. Early warning systems (2) (EWS) for disasters and other emergency systems are usually designed and used by men regardless of gender specificities, leading to the increased marginalization and vulnerability of women. For example, in some cases, EWS meeting invitations are available for one person per household and warning messages are sent to one phone per household. This means that most invitations and messages are sent to men as cultural norms assume the oldest man is the default representative of household. These EWS practices perpetuate the assumption that the 'head of the household' (man) relays messages to other family members. “Gender unaware approaches have a likelihood of perpetuating and compounding gender inequality, formalizing men as decision-makers (and erasing non-traditional households)” (3).

All these factors restrict the possibility for women and girls to know, anticipate and prepare for a pending disaster. Migration also often presents more challenges for them: 1. as they usually carry family and household responsibilities including taking care of their dependent children and elderly relatives, it is more difficult for them to choose to leave and organise their departure; 2. but also because they face major gender-based pressure during displacement. They have less access to relief resources (shelter, water and food), have specific sanitation and sexual and reproductive health needs that often go unmet, and are more likely to endure gender-based violence (4) such as forced-marriage, domestic and sexual violence, exposure to trafficking, etc. Their physical, emotional and mental health may deteriorate, in part because of exposure to violence, the loss of social support networks and heavy caregiving burdens, which can increase anxiety, post-traumatic stress and other illnesses.

CARE’s gender-transformative approach to climate-induced displacement

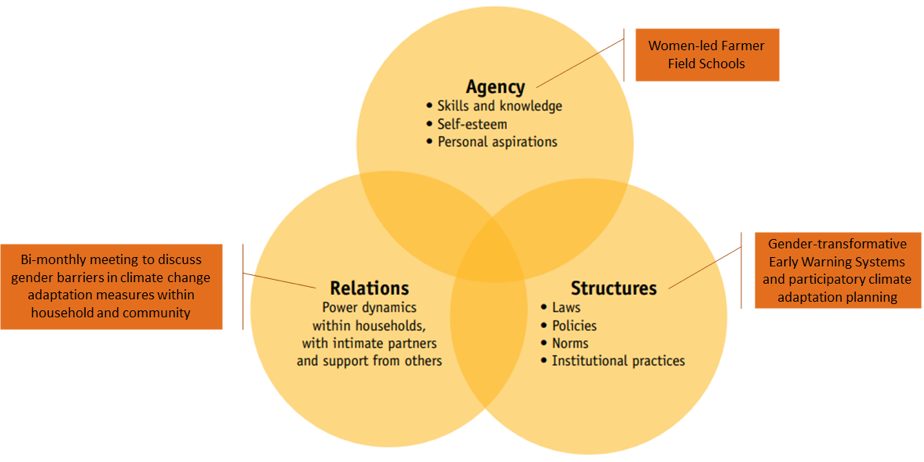

CARE defines women empowerment as the sum of changes needed for a woman to realize her full human rights, the interplay of changes in:

- Agency: her own aspirations and capabilities

- Structures: the environment that surrounds and conditions her choices

- Relations: the power relations through which she negotiates her path

The project Where the Rain Falls, conducted by CARE in India from 2014 of 2019, is a good example illustrating how to address women’s vulnerabilities in the face of climate change via these key elements.

CARE India has worked with women and girls to enhance their capacities, capabilities and confidence to adapt to climate change through women-led Farmer Field Schools (5), promoting sustainable agricultural practices and rainwater harvesting, and holding functional literacy and leadership sessions. The project also supported the creation of inclusive and effective collectives to facilitate access to opportunities, entitlements, resources, services, and markets (Agency).

A key aspect of CARE’s approach for gender transformation is to engage men and boys in women’s empowerment, in order to ensure mutual sensitization and collective responsibility. To this end, this project promoted equitable decision-making through gender dialogues, bi-monthly discussion sessions within the communities, challenging existing gender norms and practices on a range of subjects (workload distribution, financial decision making within household, marriage practices, etc). The project also supported male champions to advocate on gender equality issues.

At the end of the project, CARE observed an evolution within communities and households, with increased support and consideration between women and men and more equitable workload distribution, with 77% women reporting active participation in key decision making at household and community level (Relations).

Finally, improving governance and access to resources and support mechanisms is crucial to establish an enabling policy environment. The project implemented a model of participatory climate adaptation planning, engaging women farmers and marginalized groups, allowing them to access and understand climate information. As a result, they now actively participate in local governance fora, contribute to decision-making processes, and can receive financial support from government schemes (Structures).

After several years of programme implementation, there has been an increase in income from agriculture production (33%), a decrease in food insecurity (850 households have diversified their livelihoods through alternative income generation activities, allowing greater resilience if the harvest of a seed type is compromised for example), and a decrease in the number of days of seasonal migration (almost down by a third, from 31 days to 12 days per year).

CARE tools for gender transformative programming

At each step of a project’s cycle, CARE teams use tools to ensure gender considerations are fully integrated and addressed. CARE systematically applies a Gender Marker to assess and monitor the integration of gender equality throughout projects. CARE teams also use participatory risk assessment tools, such as the Gender-sensitive Climate Vulnerability and Capacity Analysis. CARE’s Rapid Gender Analyses (RGAs), gender and conflict analyses, and emerging approaches like ‘Women Lead in Emergencies’, a flagship CARE programme looking at women’s leadership in humanitarian settings, also add a gender-lens to prevention and adaptation efforts. For further information, see our full analysis and toolkit on Gender in our website “Gender in Practice”.

Recommendations

Gender-transformative climate change adaptation actions, including climate-smart disaster risk reduction and resilience-building, can prevent and reduce forced displacement. Applying effective adaptation measures to extreme weather and slow-onset events also protects fundamental human rights. As the Office of the High-Commissioner of Human Rights (OHCHR) stated, these actions tackle the root causes of displacement seeking “to protect rights, strengthen protection systems and reduce risks and exposure” (6).

Immediate action is needed to put women and girls at the centre of concerted efforts to build communities’ resilience to climate change, and to help those who have already been affected by climate-induced displacement. CARE's recommendations are as follows:

- In addition to systematic disaggregation of data by gender and age, researchers and professionals should boost research efforts towards achieving a better understanding of the differentiated impacts of climate change on women and girls. Research is essential to inform a more tailored response in our emergency aid, climate adaptation and risk reduction efforts. An increased understanding of particular gender-related risks will reveal the extent to which some structures are gender unequal and contribute to sustainably change the systems in place. As the largest research project on climate change and migration to have been funded by the European Commission's Horizon 2020 programme, the HABITABLE project aims to contribute to this much needed evidence base.

- Governments and practitioners must ensure that women and girls are able to play meaningful roles in shaping more ambitious climate resilience, displacement prevention and response policies and localized programmes but also hold actors accountable:

- Governments must ensure that organisations that represent women and girls and promote gender equality play an influential role in the design, implementation and evaluation of policies and plans relevant to climate and displacement (climate policies, national adaptation and disaster risk reduction action plans) and that these fully integrate gender equality efforts, in line with the UNFCCC Gender Action Plan adopted at COP25.

- Practitioners and policy makers should revisit planning and programming mechanisms at all levels when addressing climate-induced displacement to effectively enable all community members, especially those who are most vulnerable, to prevent and withstand climate shocks and reduce the pressure to leave their homes if they do not wish to do so. As much as possible, local communities, including women and girls, need to be leading such measures suitable to the local circumstances. This will enable gender-responsive needs assessments, humanitarian programming plans and accountability mechanisms, such as peer reviews and after-action reviews, to genuinely include women’s and girls’ perspectives. Rapid Gender Analyses must be adapted to climate crises, including mass displacement events, as well as used in complex crises.

- Governments and the international community must advance the national and international legal and policy framework so that it comprehensively addresses climate-induced displacement and provides protection for climate displaced people, particularly women, girls and highly vulnerable groups. Synergies and gaps between existing institutions and legal frameworks in the displacement and climate change context should be identified (UN Security Council, UNFCCC Warsaw International Mechanism on Loss and Damage, the Global Compact for Migration, the Global Compact on Refugees, the UN Human Rights Council, and other fora). This must also improve the coordination of humanitarian actors and other practitioners involved in climate change action on the ground, within and beyond the UN system. National level institutions must enhance collaboration and coordination across standard thematic boundaries.

The international community and individual governments need to better respond to the challenges faced by climate change and related forced displacement. Such a response must include preventive action, provide protection to those who are affected and suffer from loss and damage, and ensure the rights of those who migrate whether by choice or by force.

CARE has long been advocating for ambitious national and international climate policies and for a significant scale up of adaptation finance from developed countries, and will continue to do so until the impacts of climate change are significantly reduced. Climate policies urgently need to support the implementation of the Paris Agreement, but also gender transformative approaches that empower women as leaders of adaptation, climate resilience programmes that can prevent displacement, and emergency response interventions through the Grand Bargain and other global humanitarian agreements.

The authors would like to thank Clotilde Coussieu, intern with CARE in 2021, for her valuable contribution to this article.

References

(1) When supporting adaptation capacities of vulnerable communities, CARE is particularly attentive to integrating a gender-transformative, not just a gender-sensitive, agenda. The transformative approach includes policies and programmes that challenge and change inequitable gender norms and relations to promote equality. It requires the resources, willingness and capacity to institutionalize transformative programming. See for further information “CARE. 2019. Gender-Transformative Adaptation” https://careclimatechange.org/gender-transformative-adaptation/

(2) Early Warning System is defined as « an integrated system of hazard monitoring, forecasting and prediction, disaster risk assessment, communication, and preparedness activities, systems, and processes that enables individuals, communities, governments, businesses, and others to take timely action to reduce disaster risks in advance of hazardous events » (UNISDR)

(3) For further information, see Brown et al., (2019) Gender Transformative Early Warning Systems: Experiences from Nepal and Peru, Rugby, UK: Practical Action https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/Gender%20Transformative%20Early%20Warning%20Systems.pdf

(4) IUCN, (2020): Gender-based violence and environment linkages The violence of inequality. https://portals.iucn.org/library/node/48969.

(5) According to the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), Farmer Field School (FFS) is an « interactive and participatory learning by doing approach. Participants enhance their understanding of agro-ecosystems, which leads to production systems that are more resilient in local conditions and optimize the use of available resources. » You can learn more about FFS on the FAO’s dedicated platform

(6) OHCHR (2018): Addressing human rights protection gaps in the context of migration and displacement of persons across international borders resulting from the adverse effects of climate change and supporting the adaptation and mitigation plans of developing countries to bridge the protection gaps - Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. https://www.right-docs.org/download/70477/

Sources

- Brown et al., (2019) Gender Transformative Early Warning Systems: Experiences from Nepal and Peru, Rugby, UK: Practical Action https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/Gender%20Transformative%20Early%20Warning%20Systems.pdf

- IUCN, (2020): Gender-based violence and environment linkages The violence of inequality. https://portals.iucn.org/library/node/48969

Toolkits:

- Making it Count: Integrating Gender Into Climate Change and Disaster Risk Reduction : a practical how-to-guide

- CARE’s approach Gender in Emergency

Practices:

- Promising Practices toward Gender Justice, Resilience and Food/Nutrition Security

- FAO’s Global Farmer Field School Platform

Other sources: