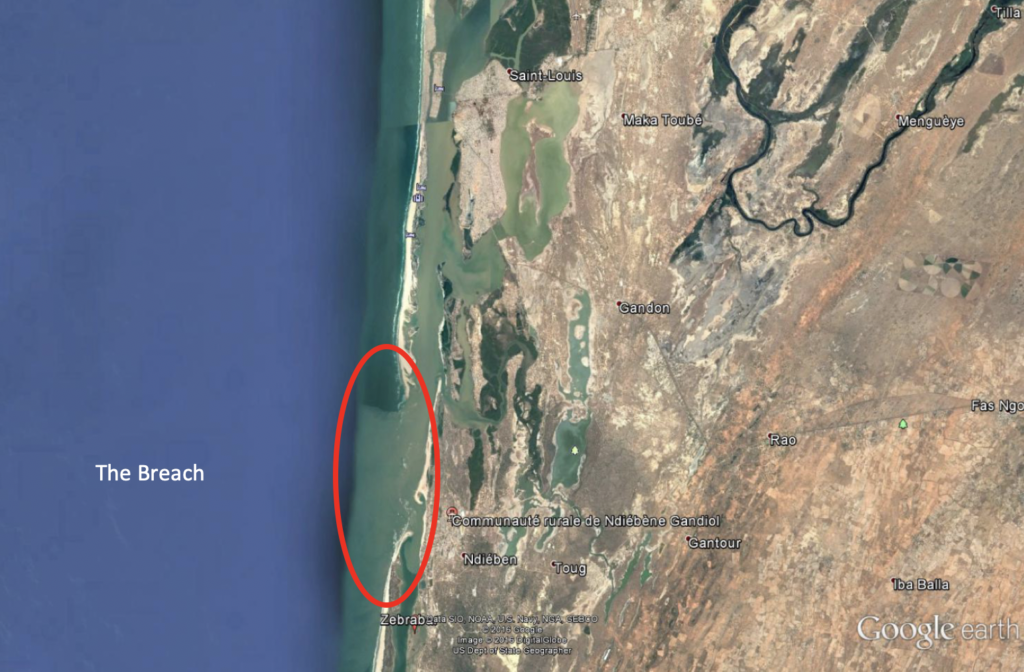

In 2003, the city of Saint-Louis in Northern Senegal had to deal with the threat of serious flooding. To manage this menace of the Senegal River, the authorities decided to dig a flow channel on the Langue de Barbarie to evacuate the surplus water to the Atlantic Ocean. This channel is now commonly called the Breach. Initially, the width of the Breach measured four meters when it was built, but quickly expanded in an unexpected direction southward, reaching 5,200 meters in 2015 (Syand al., 2015). Outside the city of Saint-Louis, the locality of Gandiol has been particularly exposed to coastal erosion following the uncontrolled expansion of the Breach. Following the enlargement of the Breach, two villages were destroyed by the sea and others are threatened (Sy and al., 2015). Coastal erosion occurs periodically through marine submersion events that destroy habitats and ecosystems. The consequences of these submersions, such as the salinization of soils and groundwater, are slow processes. In addition to the destruction of habitats, there are also negative consequences on fishing, market gardening and animal husbandry.

Leaving

In this context, where the assurance of livelihood becomes difficult, households must adapt to the new environment. For those who have the necessary resources, permanent migration of one or more members of the household represents an adaptive response. Indeed, migration can be a possible adaptive response to environmental stresses (Mc Leman and Smit, 2006), especially through remittances (Foresight, 2011). Migrants can help improve living conditions, mostly for populations that depend upon natural resources to survive (Adger et al., 2002). In Gandiol, the permanent migration of male family members seems to be a direct consequence of the environmental degradations caused by the Breach. Previously, migration was mainly circular and seasonal, as it was related to fishing activities. Permanent migration is therefore a new phenomenon that aims to help the family to stay in their region and to continue traditional economic activities (Tandian, 2015) through transfers of funds, practices, and technologies (Sall and al., 2011; GERM, 2017).

Supporting

Households mobilize financial transfers in different ways to adapt to the changing environment and have short-, medium- and long-term effects. The use of remittances serves primarily to diversify the source of household incomes and supports adaptation in the short and medium term. Investing remittances in new farming and fishing techniques promotes the ability of households to have a continuous minimum income over time and reduces the risk to only rely on remittances. The construction of new houses, the investments in community buildings and their maintenance by migrants, act as a vector of protection on several levels. In addition to providing shelter for families likely to be affected by marine submersion, the establishment of new buildings provides occasional work for the community. Finally, the significant emigration of men has consequences on the division of labour and on the traditional patriarchal structures of households. The active participation of women in income-generating activities guarantees a minimum of long-term livelihoods for households and promotes women's activity. These different strategies put in place in Gandiol show that migration and its consequences can function as a lever for development. Migrants are therefore agents of change.

Not coming back

By questioning the perception of migrants and non-migrants towards financial transfers and their contribution to adaptation strategies, it is possible to shed light on some elements to explain the prevalence of permanent migration as an adaptation strategy (Lietaer and al., 2020). Some individuals, especially men, may not have the freedom to choose to stay or return to the village due to social pressure. Men are mainly the household's breadwinners and must ensure food security, either through local activities or through migration. Young men are supposed to contribute to household incomes and improve the family's economic situation. Faced with the expectations of the villagers, adaptation has become a social norm internalized by migrants (Ibid). The longer the male migrant stays abroad, the more it increases the adaptive capacities in the village of origin.

The use of remittances represents forms of adaptation that often combine in a complex way. Even if migration as an adaptation strategy is not made aware as such by migrants and non-migrants, it remains essential to ensure a minimum of livelihoods.

Saint-Louis and Gandiol in 2003

Source: Google Earth

Saint-Louis and Gandiol in 2016

Source: Google Earth

Picture of The Breach taken in July 2018 with a drone

Credit: Baptiste Lelong et Loïc Brüning

Pictures of damages caused by marine submersions

Credit: Arona Fall

Credit: Loïc Brüning

References

Adger W. N., Kelly P. M., Winkels A., Huy L. Q., Locke C.,( 200)2, Migration, remittances, livelihood trajectories, and social resilience, AMBIO: A Journal of the Human Environment, 31(4), p. 358-366

Foresight. (2011). Migration and global environmental change - Future challenges and opportunities. London: Government Office for Science.

Groupe d’Etudes et de Recherches sur les Migrations et faits de sociétés (GERM). 2017. Changements climatiques et stratégies d’adaptation à Saint-Louis.

Lietaer, S., L. Brüning & C. N. Faye (2020) Ne pas revenir pour mieux soutenir ? Perceptions de la migration comme stratégie d’adaptation face aux changement environnementaux dans trois régions du Sénégal Emulations-Revue de sciences sociales, 97-113.

McLeman, R. & B. Smit (2006) Migration as an adaptation to climate change. Climatic Change, 76, 31-53.

Sall, M., M. Serigne, A. Tandian & A. Samb (2011) Changements climatiques, stratégies d’adaptation et mobilités. Evidence à partir de quatre sites au Sénégal. Working paper N°33.

Sy, B., A. Boubou, A. Sy, A. Bodian, T. Faye, S. Niang, M. Diop & M. Ndiaye. 2015. 'Brèche'ouverte sur la Langue de Barbarie à Saint-Louis: esquisse de bilan d'un aménagement précipité. L’Harmattan

Tandian, A. (2015) Variations environnementales, mobilité et stratégies d’adaptation au Sénégal. Migrations internationales: un enjeu Nord-Sud?, 22, 177.